The Spectrum of Addiction: Trauma, Healing, and Human Becoming

A unified philosophy of addiction as a survival response, a social mirror, and a path toward wholeness.

by Donovan Davidson | June 12, 2025

Addiction Is Not the Exception—It Is the Mirror

I do not believe in the phrase “once an addict, always an addict.” It casts addiction as a life sentence—an inherited flaw or moral failure to be managed but never healed. I have come to believe something radically different: addiction is not an identity—it is a strategy. A response. A survival mechanism in a world that wounds us deeply, both personally and collectively.

Addiction is not rare. It is everywhere. It is the workaholic chasing validation. It is the manipulative lover who avoids intimacy. It is the parent obsessed with control, the CEO who ignores his children and exploits his workers, the artist who can’t create without chaos. These are not separate from addiction. They are its quieter cousins.

What we call addiction is not limited to substances. It is a spectrum of human coping, shaped by trauma, culture, and nervous system dysregulation. Some reach for heroin. Others for spreadsheets. Some lie to avoid the shame of weakness; others dominate, deflect, or gaslight to prevent feeling small.

Addiction is not just a disease—it is a mirror. It reflects what we have not yet learned to face.

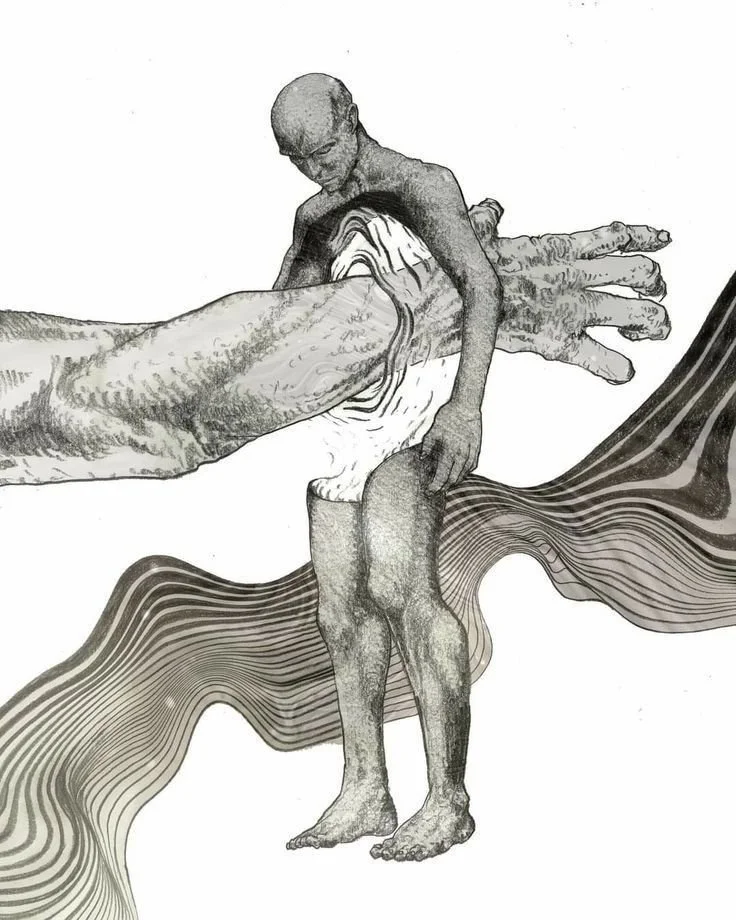

Internal Family Systems (IFS): Addiction as a Protector Part

IFS teaches that we are not singular selves—we are many. The part of me that used, that lied, that escaped—it was not evil. It was trying to protect me. In IFS, addiction is seen as a “firefighter part”—an emergency responder that rushes in to soothe the unbearable screams of exiled inner children.

Addiction is not the enemy. It is the exhausted protector. It is not trying to destroy us. It is trying to keep us alive.

Healing does not come from shaming or erasing this part. It comes from listening. From welcoming it back into relationship with the rest of us. What once coped by numbing may one day serve by creating, by nurturing, by standing guard in healthier ways.

Gabor Maté: Ask Not “Why the Addiction,” but “Why the Pain?”

Dr. Gabor Maté reminds us that addiction is never about pleasure—it is about escaping pain. Through his lens of Compassionate Inquiry, we learn to ask better questions:

Not “what’s wrong with you?” but “what happened to you?”

Each addictive pattern is a coded cry from a wounded place within. A call for connection. For safety. For coherence.

Healing is not just about stopping the behavior. It is about re-learning how to feel—to feel pain without drowning, to feel loneliness without vanishing, to feel anger without destruction.

Addiction fades not when we conquer it, but when we understand what it was protecting.

Polyvagal Theory: Addiction as a Body Trying to Feel Safe

Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory offers the somatic dimension. Many who use substances or behaviors compulsively are not chasing highs—they are trying to regulate a dysregulated nervous system. Trauma traps the body in loops of fight, flight, or shutdown.

Cocaine simulates mobilization—sympathetic arousal.

Opioids mimic parasympathetic safety—numbness, relief.

Alcohol muddles collapse and connection.

What looks like addiction is often a biological attempt to self-soothe, to re-enter a state of felt safety. Without co-regulation, community, or nervous system literacy, the person is left to improvise—with often devastating consequences.

Recovery becomes a physiological retraining: breath, rhythm, safe touch, and attunement—learning to find regulation without needing the fix.

The False Divide: Substance vs. Behavioral Addictions

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) splits addiction into “substance use” and “behavioral,” but the lived reality is more unified. The same psychological and biological loops underlie both:

Emotional trigger

Overwhelm

Behavior as regulation

Temporary relief

Shame

Repetition

The difference between a heroin addict and a CEO obsessed with power is not structural—it is socially sanctioned visibility. One gets treatment. The other gets rewarded.

Manipulation is not strategy—it’s an addiction to control. Narcissism is not confidence—it’s an addiction to validation. Workaholism is not ambition—it’s an addiction to avoidance. These behaviors, like substance use, arise to fill unmet developmental needs—to shield us from the annihilation of not being seen, soothed, or safe.

Societal Addiction: Culture, Capitalism, and Collective Wounding

Addiction does not occur in a vacuum. It is not only personal—it is political.

Racial capitalism, intergenerational trauma, cultural narcissism, and systemic neglect do not exist on the periphery of addiction—they are its soil, its architecture, its invisible scaffolding. The world teaches us early that love must be earned, that pain must be hidden, that vulnerability must be punished. These forces weave through the lives of those most vulnerable, not as abstract social concepts, but as felt conditions: inherited fear, inherited absence, inherited pressure to perform, assimilate, survive.

They manufacture scarcity—not just of material resources, but of presence, care, tenderness, and belonging. They teach us early that love is conditional, that silence is safer than grief, and that the only acceptable emotions are those that do not make others uncomfortable. In this landscape, addiction is not an aberration—it is a perfectly logical response to a world that fragments the self before it even forms.

Wherever the world denies worth, addiction rushes in to supply it—fleeting, temporary, but tangible. In a society driven by extraction—of labor, of bodies, of attention—addiction mirrors the same cycle: take more, feel less, collapse, repeat. The heroin user and the corporate executive may appear to live in opposite worlds, but both may be numbing the same wound: the unbearable weight of disconnection. One is punished; the other is praised. But both are caught in a system that has made it unsafe to feel.

These forces don’t just create trauma—they make it unspeakable. They leave us with pain we cannot name, stories we cannot tell, and bodies we cannot trust. And so we reach for what can hold us, even if it kills us. Because at least the substance, the behavior, the fixation doesn’t abandon us—not the way the world did.

And when we finally try to heal, we are told the problem lives within us. That we must take moral inventory, control our urges, fix our brokenness. But what if the problem is not only personal? What if the pain we carry is not just ours, but collective? What if addiction is a scar stitched across generations, encoded in silence, reinforced by systems that profit from our ache?

We must ask:

What does it mean to pathologize heroin use while celebrating billionaires addicted to domination?

What do we call a society that promotes burnout, disconnection, and extraction?

What if addiction is not the sickness—but a symptom of a sick world?

To heal addiction, we must not only look inward, but outward. We must reimagine the conditions that make it necessary.

A Unified Philosophy of Healing: Integration Over Abstinence

Recovery is not a return to who we were. It is the integration of what we once exiled.

From fragmentation to inner dialogue (IFS)

From shame to curiosity (Maté)

From threat to safety (Polyvagal)

From suppression to wholeness (spectrum view)

Recovery is not abstinence—it is presence. It is staying. Feeling. Listening.

It is unlearning the lie that our worth is conditional on perfection, performance, or pleasure. It is transforming coping into connection. Fixation into flow. It is making peace with the parts of us that once only knew how to run.

Closing Meditation

I am not an addict.

Addiction is not who I am—it's a spectrum that lives within us all.

I am a human who once adapted to survive.

I am learning to stay—with discomfort, with tenderness, with truth.

I do not fear the parts of me that once sought escape.

I meet them now with breath, with presence, with love.

This is not abstinence.

This is wholeness returning.

This is me, becoming.